Memory management

Memory management is a critical part of any operating system kernel. Providing a quick way for programs to allocate and free memory on a regular basis is a major responsibility of the kernel. There are many implementations for allocating physical memory including bitmaps, buddy allocation and using tree structures or queues/stacks.

For an overview of memory allocation models, and methods of allocating memory, see Program Memory Allocation Types. If you are looking for heap type memory management, which is the allocation of smaller chunks of memory not on large boundaries then see the Heap page. A heap is commonly implemented (in the popular way of thinking) not only in the kernel, but also in applications - in the form of a standard library. For a discussion of automatic memory management methods, see Garbage Collection.

Address Spaces

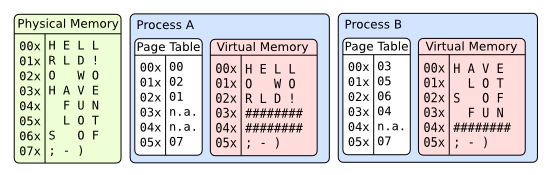

Many platforms, including x86, use a memory management unit (MMU) to handle translation between the virtual and physical address spaces. Some architectures have the MMU built-in, while others have a separate chip. Having multiple address spaces allows each task to have its own memory space to work in. In modern systems this is a major part of memory protection. Keeping processes' memory spaces separate allows them to run without causing problems in another process's memory space.

Physical Address Space

The physical address space is the direct memory address used to access a real location in RAM. The addresses used in this space are the bit patterns used to identify a memory location on the address bus.

In this memory model, every executable or library must either use PIC (position-independent code), or come with relocation tables so jump and branch targets can be adjusted by the loader.

The AmigaOS used this memory model, in absence of a MMU in early 680x0 CPUs. It is most efficient, but it does not allow for protecting processes from each other, thus it is considered obsolete in today's desktop operating systems. It is also prone to memory fragmentation; certain embedded systems still use it, however.

Virtual Address Space

The advent of MMUs (Memory Management Units) allows virtual addresses to be used. A virtual address can be mapped to any physical address. It is possible to provide each executable with its own address space, so that memory always starts at 0x0000 0000. This relieves the executable loader of some relocation work, and solves the memory fragmentation problem - you no longer need physically continuous blocks of memory. And since the kernel is in control of the virtual-to-physical mapping, processes cannot access each other's memory unless allowed to do so by the kernel.

Memory Translation Systems

The x86 platform is unique in modern computer systems in that it has two methods for handling the mapping between virtual and physical addresses. The two methods, paging and segmentation, each use a very different system to manage memory mapping.

Segmentation

- Main article: Segmentation

Segmentation is not commonly available in mainstream systems except for the x86. In protected mode this method involves separating each area of memory for a process into units. This is handled by the segment registers: CS, DS, SS, ES, FS, GS (CodeSegment, DataSegment, StackSegment, the rest are ExtraSegments).

Paging

- Main article: Paging

Having an individual virtual-to-physical mapping for each address is of course ineffective. The traditional approach to virtual memory is to split up the available physical memory into chunks (pages), and to map virtual to physical addresses page-wise. This task is largely handled by the MMU, so the performance impact is low, and generally accepted as an appropriate price to pay for memory protection.

Virtual Memory

The next step is, instead of reporting an "out of memory" once the physical memory runs out, is to take pages that are not actually accessed currently, and write them to hard disk (swapfile or -partition) - freeing up the physical memory page. This is referred to as "paging out" memory.

This requires additional bookkeeping and scheduling, introduces a severe performance hit when a process accesses a page that's currently swapped out and must be swapped in again from hard drive, and requires some smart design to run efficiently at all. Do it wrong, and this one part of your OS can severely impact your performance.

On the other hand, your "virtual address space" grows to whatever your CPU and hard drive can handle. In concept, CPU caches and RAM simply become cache layers on top of your hard drive, which represents your "real" memory limitation.

Page swapping systems relies on the assumption that, at a given time, a process does not need all of its memory to work properly, but only a subset of it (like, if you're copying a book, you certainly don't need the whole book and a full set of blank pages: the current chapter and a bunch of blank page can be enough if someone can bring you new blank pages and archive the pages you've just written when you come short on blank pages, or bring you the next chapter when you're almost done with the current one). This is known as the working set abstraction. In order to run correctly, a process requires at least its working set of physical pages: if less pages are provided to the process, there's a high risk of thrashing, which means the process will be constantly requiring pages to be swapped in -- which forces other pages from this process's working set to be swapped out while they should have remained present.

Note: there are alternatives to page-swapping like segments-swapping and process-swapping. In those cases, the swap is rather user-software controlled, which puts more stress on the application developer and leads to longer swapping burst as the logical things to be swapped are bigger than 4K pages.

Other note: mainstream desktop OSes have a speculative algorithm that tries to reduce the 'page miss' frequency by loading *more* than what is required, and hoping that these extra pages will be useful. As programs tend to have *localized* access and that disks can read a track of N sectors faster than N independent sector, speculative swap-in may pay.

See Also

Articles

- Detecting Memory (x86)

- Garbage collection

- Memory Allocation

- Page Frame Allocation

- Writing a memory manager - a tutorial

- Brendan's Memory Management Guide

Threads

External Links

- AMD Systems Programming Documentation Chapters 3 & 4 of Volume 2

- Intel Systems Programming Documentation Chapters 3 & 4 of Volume 3A

- LinuxMM - A wiki documenting memory management projects and development

- Memory Management Articles - Bona Fide OS Development Tutorials on Memory Management

- Memory management on Wikipedia.

- Jun 2008: Motherboard Chipsets and the Memory Map by Gustavo Duarte

- Jan 2009: Anatomy of a Program in Memory by Gustavo Duarte